{{First_Name|Explorer}}, welcome back!🚀

Despite a quieter news cycle, we saw meaningful movement in launch and orbital infrastructure, defense activity, and commercial initiatives. Op‑Ed Alert: The commercial rush into orbit is intensifying and so is the race to install data centers in space. How much sky are we willing to sacrifice? Who decides what orbit is for?

The publication is best experienced here ⬇️

Hope you enjoy this Space!

IMAGES

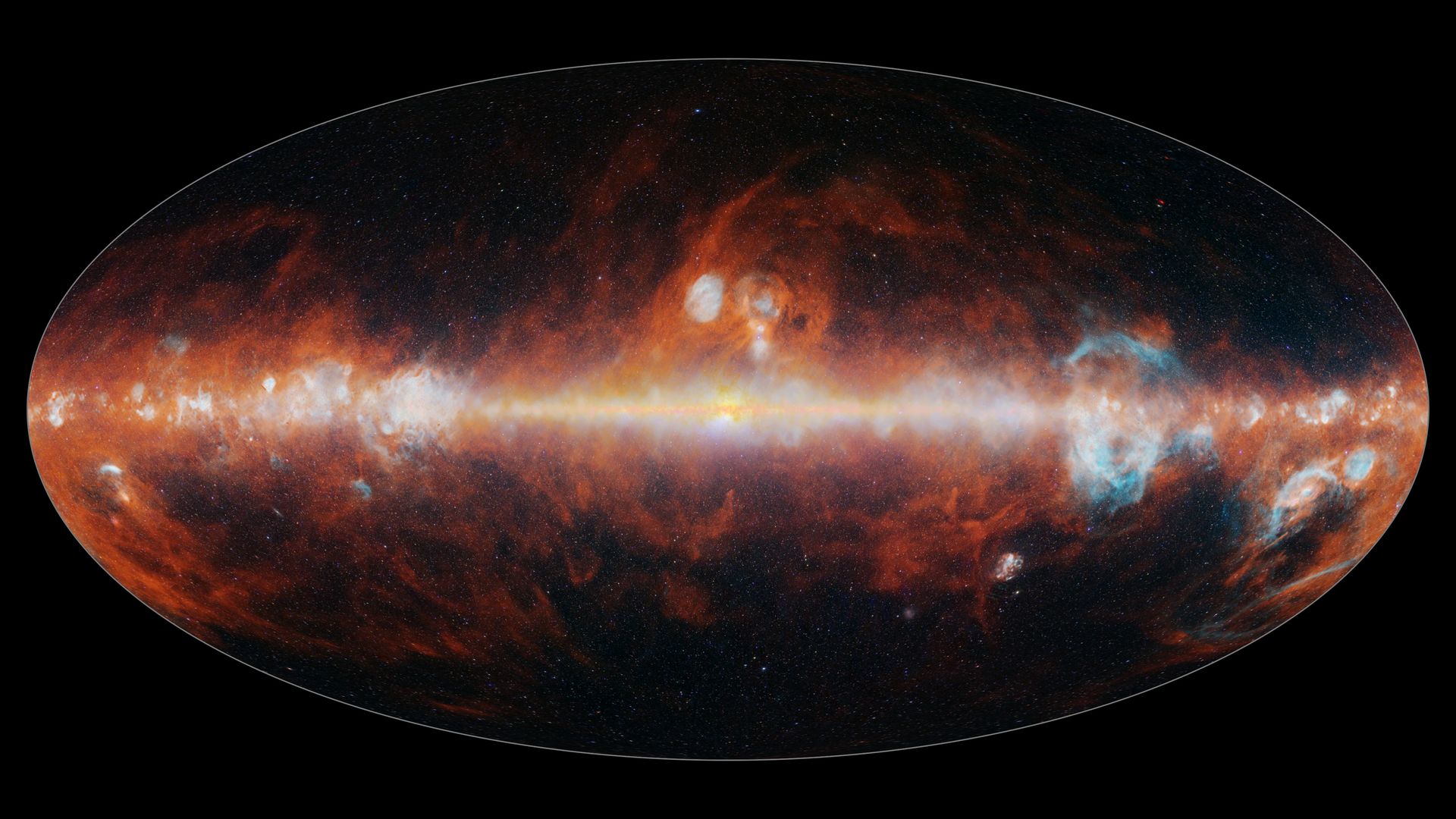

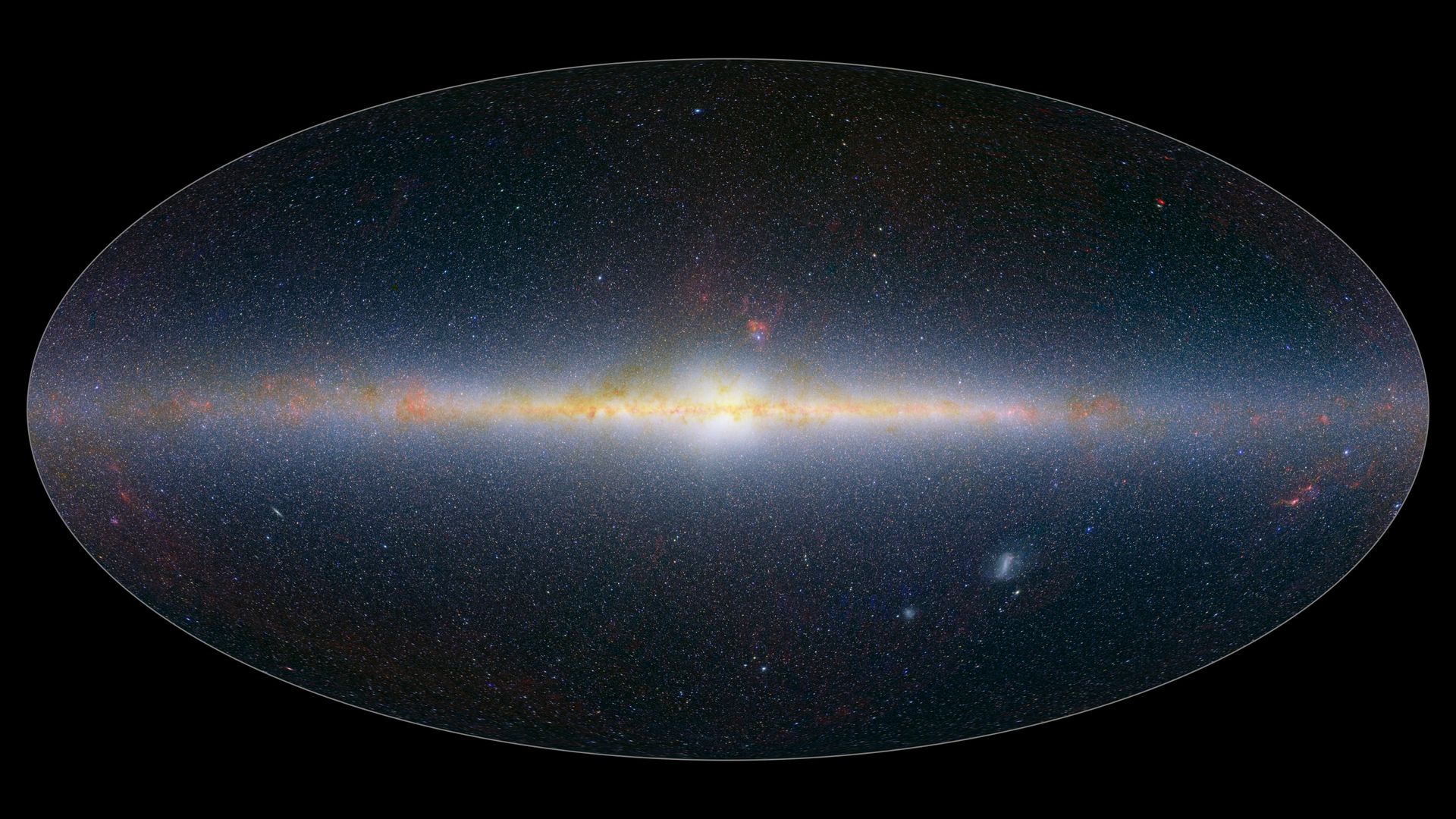

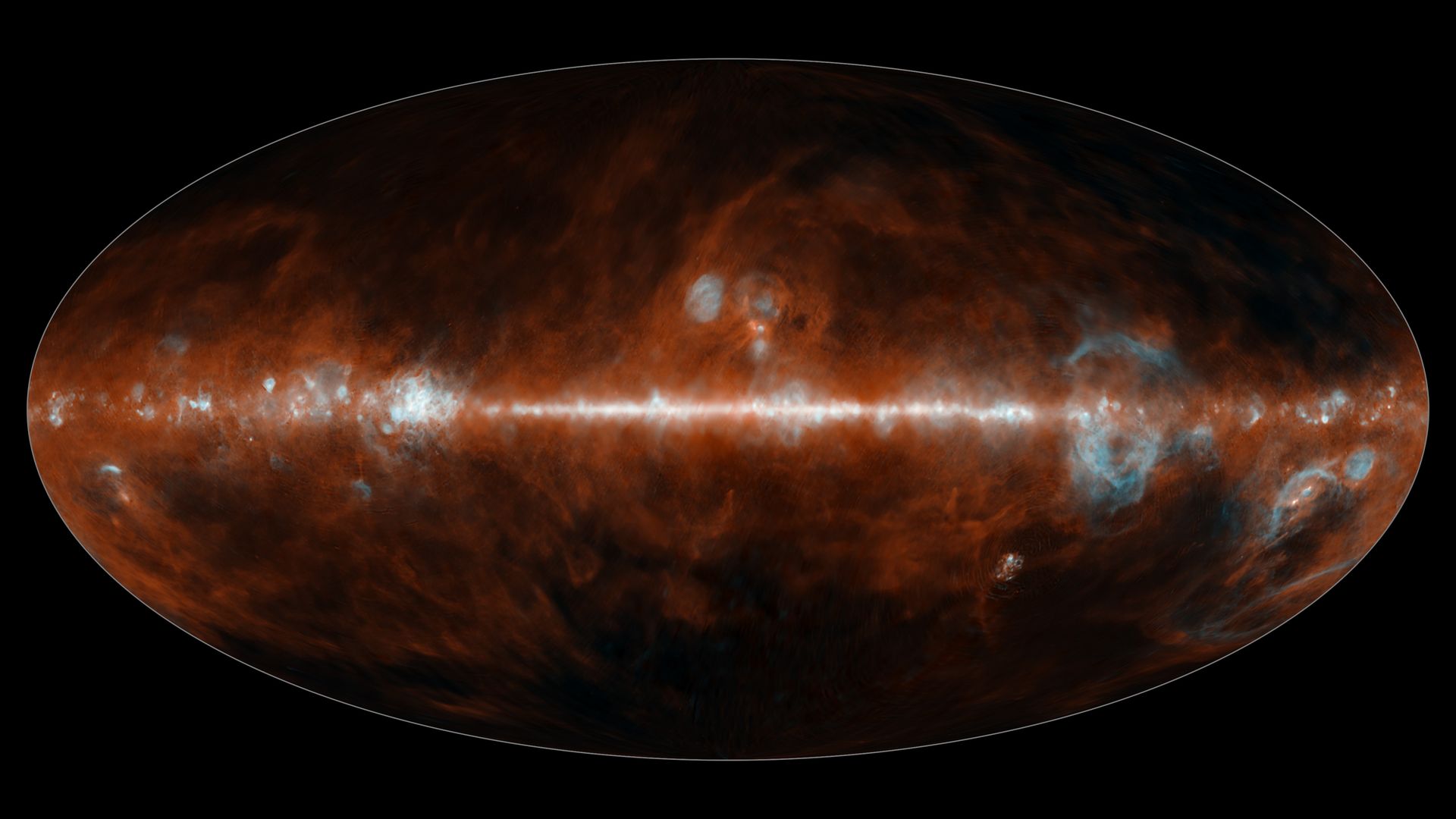

An All Sky Map : SPHEREX Space Observatory, NASA

NASA’s SPHEREx observatory has completed its first full‑sky infrared map, capturing the cosmos in 102 wavelengths that are invisible to human eyes. The composite features colors emitted by stars (blue, green, and white), emissions from hot hydrogen gas (blue) and cosmic dust (red), materials that trace star‑forming regions and the structure of the Milky Way.

SPHEREx carries six detectors, each equipped with a custom filter containing a gradient of 17 colors. Together, they capture images in 102 distinct infrared colors, effectively turning every all‑sky scan into 102 separate maps, each at a different wavelength. By analyzing these colors, the mission will estimate distances to hundreds of millions of galaxies. While many of those galaxies have already been charted in two dimensions, SPHEREx will add the missing depth information, creating a 3D map of the universe. This will allow scientists to study subtle patterns in how galaxies cluster and trace large‑scale cosmic structure. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

This SPHEREx image highlights infrared colors emitted by stars and galaxies. The telescope is surveying hundreds of millions of galaxies across the sky, using multiwavelength data to help astronomers determine their distances.

SPHEREx which stands for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer, orbits Earth about 14½ times a day, moving north to south over the poles. It captures roughly 3,600 images daily along a circular strip of sky, and as Earth orbits the Sun, the telescope’s viewing angle gradually shifts. Over six months, this motion allows SPHEREx to scan every direction in space, completing a full 360‑degree map of the sky. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Infrared light from dust (red) and hot gas (blue), essential for forming stars and planets, is captured in this SPHEREx image. These structures cover vast areas but are undetectable in visible wavelengths.

It will complete three additional all-sky scans during its two-year primary mission, and merging those maps together will increase the sensitivity of the measurements. The entire dataset is freely available to scientists and the public. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

These data will also help scientists probe conditions in the first fraction of a second after the big bang, and study how galaxies evolved over 13.8 billion years. The mission’s first map marks the foundation of a legacy dataset designed to support research on everything from cosmic inflation to the origins of water and organic molecules. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

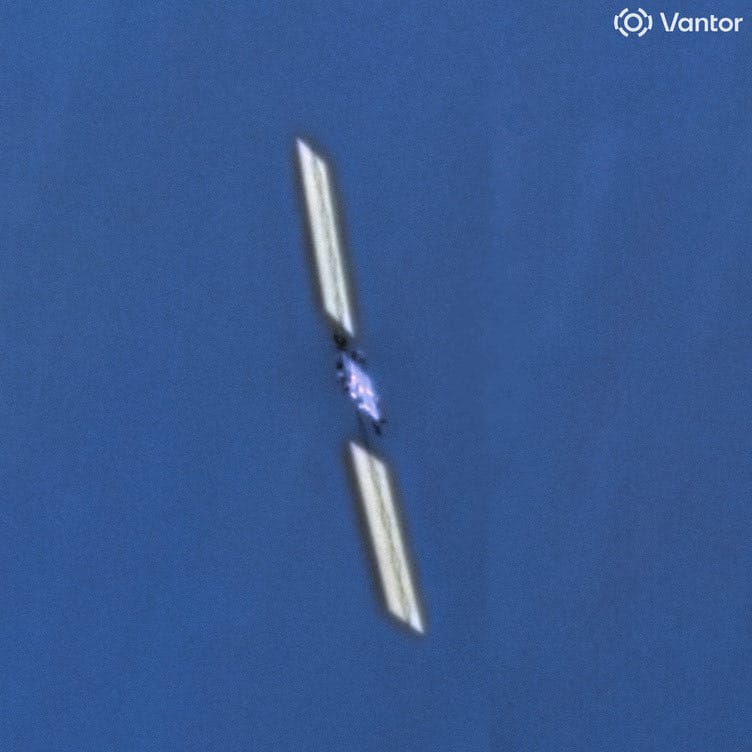

Uncontrolled Descent of a SpaceX Starlink Satellite : Vantor

A high‑resolution image from Vantor’s WorldView‑3 satellite shows a malfunctioning SpaceX Starlink spacecraft after an in‑orbit anomaly on December 17 caused it to lose contact and vent its propulsion tank.

The failure left the satellite tumbling and descending toward Earth, where it is expected to burn up in the atmosphere within weeks, according to SpaceX. Vantor captured the photo from about 150 miles away to help assess the satellite’s condition, offering a rare close‑up look at a damaged spacecraft in low Earth orbit. (Credit: Vantor)

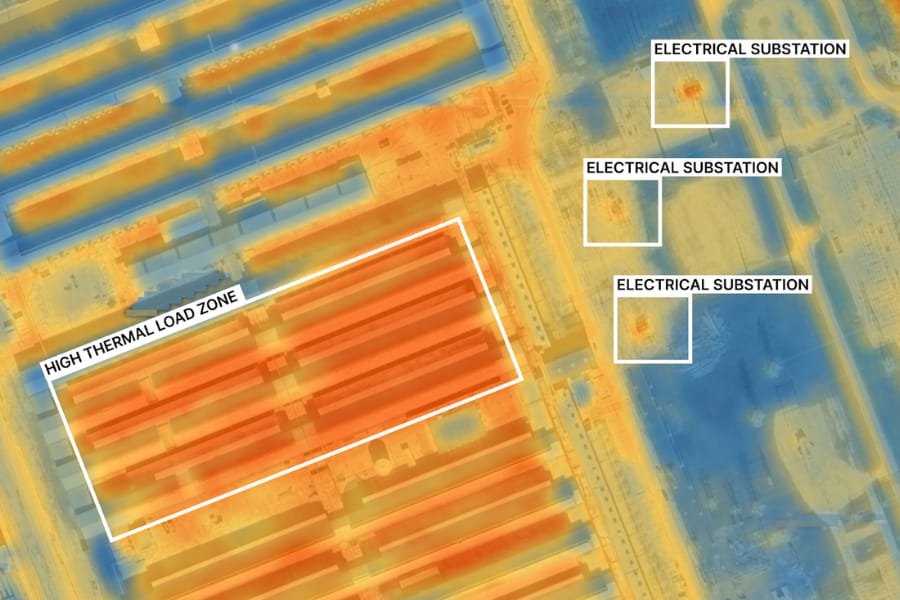

Heat Leaking from the Largest US Crypto‑Mining Center : SatVu

A new high‑resolution thermal image from the UK-based satellite imagery provider, SatVu, reveals the operational footprint of one of the largest Bitcoin‑mining data centers in the United States, located in Rockdale, Texas. Captured at 3.5‑meter resolution, the image shows intense heat signatures from cooling systems, substations, and high‑load infrastructure, offering a rare look at real‑time energy use inside a facility long criticized for its massive electricity consumption and environmental impact.

The thermal map highlights how waste heat escapes into the surrounding environment, making visible the scale of operations that typically remain hidden from public view. The newly released image reveals distinct thermal signatures across rooftop chillers, transformers, and electrical yards, clearly outlining which parts of the facility are active and which remain idle. As energy‑hungry sectors like AI, cloud computing, and cryptocurrency mining continue to expand, these patterns offer a rare view into how operational loads shift over time, how new phases come online, and how activity is distributed across the campus. (Credit: SatVu)

SCIENCE

NASA’s AVIRIS‑5 Sensor Hunts for Critical Minerals From 60,000‑Feet as Demand Grows for EVs and Electronics

A pilot signals to a crew member before departing NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, on Aug. 21, 2025. On board the high‑altitude ER‑2 is one of the most advanced imaging spectrometers currently in use. (Credit: NASA/Christopher LC Clark)

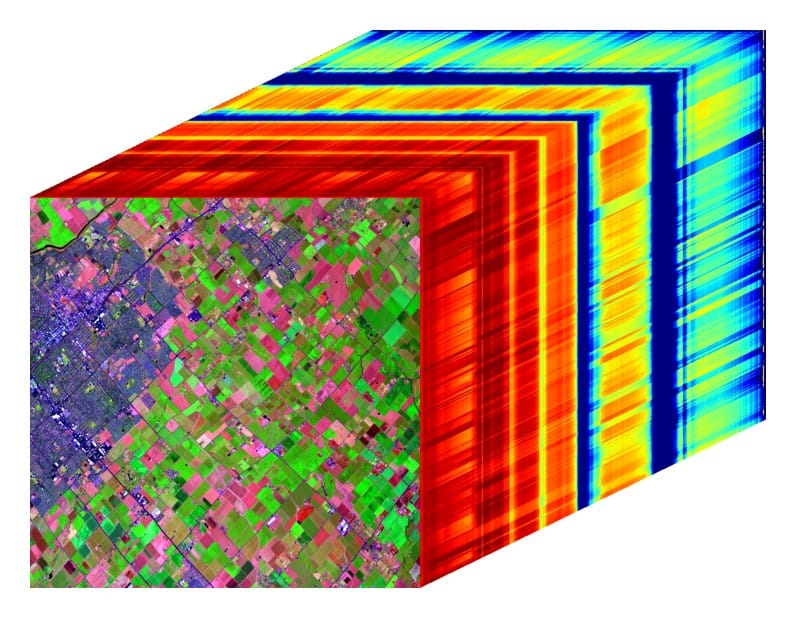

NASA has begun deploying a new imaging spectrometer, AVIRIS‑5, to survey surface deposits of lithium and other critical minerals across the American West. The Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer-5 or AVIRIS‑5, mounted in the nose of a high‑altitude ER‑2 aircraft, is a microwave‑sized instrument that operates at about 60,000 feet, collecting reflected sunlight across hundreds of wavelengths to identify the “spectral fingerprints” of specific minerals. The sensor is the latest in a decades‑long line of JPL‑developed spectrometers originally designed for planetary exploration, now adapted for terrestrial resource mapping. With twice the spatial resolution of the previous model, AVRIS-5 can distinguish features from under a foot (30 centimeters) up to roughly 30 feet (10 meters) across. Critical minerals include aluminum, lithium, zinc, graphite, tungsten and titanium, which feed into manufacturing supply chains for key technologies, including semiconductors, solar power systems, and electric‑vehicle batteries.

These image cubes show the large data volumes produced by JPL’s imaging spectrometers. The front panel captures roads and agricultural fields near Tulare, California, observed by AVIRIS‑5 during a checkout flight earlier this year, while the side panels display the spectral signature recorded at each point in the scene. (Credit: NASA/JPL‑Caltech)

The flights support Geological Earth Mapping Experiment (GEMx), a joint NASA and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) campaign described as the largest airborne mineral‑mapping effort undertaken in the United States. This year, the campaign has accumulated more than 200 hours of high‑altitude survey flights over Nevada, California, and other Western states. Since 2023, the project has surveyed extensive desert regions where lithium‑bearing clays and other strategic materials are likely to occur. Since then the campaign has covered over 950,000 square kilometers/366,000 square miles. NASA frames the effort as a way to improve national understanding of domestic mineral resources essential for electronics, clean‑energy systems, and defense technologies.

GEMx serves as the airborne arm of the USGS Earth Mapping Resources Initiative (Earth MRI), which aims to modernize national surface and subsurface mapping.

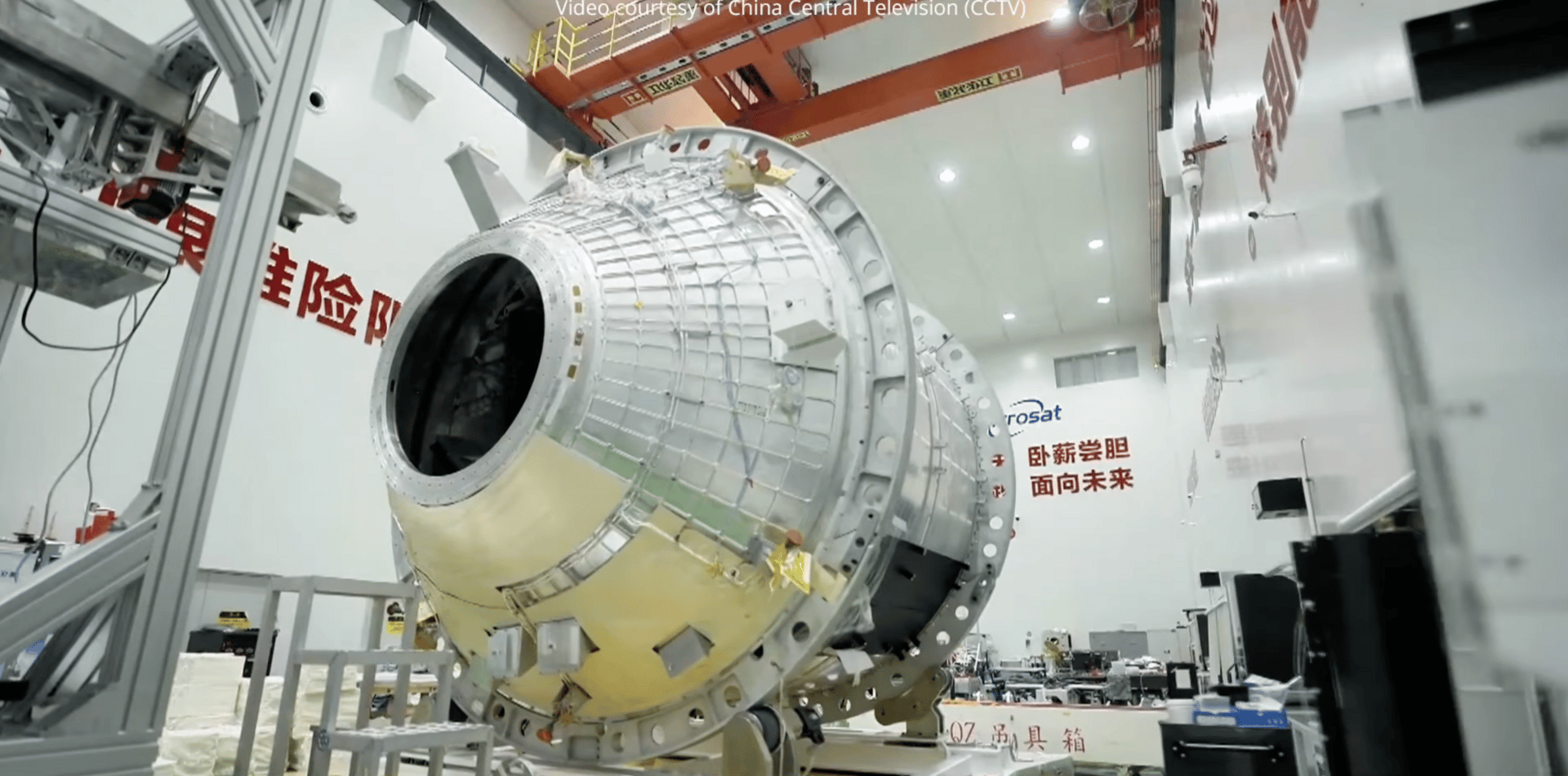

China Prepares Qingzhou Cargo Spacecraft Prototype to Expand Tiangong Resupply Capacity

22 December, 2025

China is advancing development of its next‑generation Qingzhou cargo spacecraft, aiming to begin full prototype production in 2026 after completing key technology verifications and entering integrated testing. Developed by the Innovation Academy for Microsatellites of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IAMCAS), Qingzhou is designed as a lighter, lower‑cost complement to the existing Tianzhou freighter, supporting long‑term operations of the Tiangong space station. Qingzhou’s maiden flight, originally planned for earlier in 2025, has slipped, with the spacecraft now scheduled to launch next year.

Qingzhou uses a single‑module design to maximize space and reduce mission costs. Its four cargo racks offer 40 storage compartments with 27 cubic meters of usable volume for supplies, equipment, and research payloads. The spacecraft also includes five 60‑liter cold‑chain units for crew food and temperature‑sensitive biological samples. The 5‑tonne vehicle features a 3.3‑meter diameter, modular internal layout, and the ability to carry up to 1.8 tonnes of supplies while returning roughly two tonnes of waste to Earth.

China views the system as part of a broader effort to expand Tiangong’s logistics capacity as the station moves toward a decade of continuous crewed operations. Developers say the vehicle has met its core performance targets, but additional testing and integration work pushed the schedule beyond its initial window. After a successful design review in mid‑2025, the program moved into early manufacturing, with engineering models now expected to be ready for assembly in early 2026.

China Tests Long March 12A Reusable Rocket With Successful Orbital Flight and Failed Booster Recovery

The Long March 12A Y1 vehicle lifts off from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on Dec. 22, 2025. (Credit: CASC)

22 December, 2025

China conducted the first launch of its state‑owned reusable Long March 12A rocket late December 22, successfully reaching orbit but failing to recover the first‑stage booster. Liftoff occurred from Jiuquan’s Dongfeng Commercial Space Innovation Test Zone, with the booster targeting a landing site roughly 250 kilometers downrange in Gansu province. Satellite imagery and social‑media photos indicated the stage came down about two kilometers off‑pad. Official confirmation of orbital insertion arrived more than two hours after launch, with developer Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) stating the mission still yielded valuable engineering data for future recovery attempts.

The methane‑fueled Long March 12A is part of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation’s (CASC) broader push toward reusability, alongside planned Long March 10 variants expected in 2026. The flight follows a similar attempt on December 3 by Landspace’s Zhuque‑3, which also reached orbit but failed during its landing burn. Both efforts show technical progress, though China remains early in developing reusable launch capability.

ISRO Successfully Deploys AST SpaceMobile’s BlueBird‑6 Direct‑to‑Device Satellite to LEO

India’s LVM3 vehicle launches AST SpaceMobile’s BlueBird‑6 satellite, designed for direct‑to‑device connectivity, on Dec. 23, 2025. (Credit: ISRO)

23 December, 2025

India’s LVM3‑M6 mission successfully placed AST SpaceMobile’s BlueBird‑6 satellite into low Earth orbit, marking the heaviest payload at 6,100 kilograms/13,450 pounds, the launcher has carried to date. The three‑stage vehicle deployed the spacecraft into a 521‑kilometer/324 miles orbit roughly 15 minutes after liftoff.

BlueBird‑6 is the first of AST SpaceMobile’s next‑generation satellites and carries a communications array significantly larger than earlier models, spanning nearly 223 square-meters/2,400 square-feet. BlueBirds 1 through 5 carry 64.4 square‑meter/693 square‑feet communication arrays, the largest deployed in low Earth orbit to date.

The spacecraft is part of a planned constellation intended to provide broadband connectivity directly to standard smartphones from orbit. For ISRO, the mission highlights the LVM3’s growing relevance in the global heavy‑lift market, following earlier deployments for Chandrayaan and OneWeb. For AST SpaceMobile, it represents a scale‑up in hardware capability as the company moves from initial demonstrations toward operational infrastructure in low Earth orbit.

Russia's Energia Files Patent for Rotating Artificial‑Gravity Space Station

A conceptual rendering of a rotating space station. (Credit: Lagrangian)

24 December, 2025

Russia’s state‑owned Energia corporation has secured a patent for a spacecraft architecture designed to generate artificial gravity, outlining a rotating station concept that departs from the country’s current low‑gravity platforms. The patent describes a central axial module with both static and rotating sections, linked by a hermetically sealed flexible junction, with habitable modules arranged radially around it. When spun at about five revolutions per minute and with a radius of 40 meters/131 feet, these modules would create centrifugal force equivalent to about 0.5 g, a level intended to mitigate the physiological degradation associated with long‑duration missions. Much like the ISS, such a space station would require multiple launches for each module and assembly in orbit.

Top-down schematic of a manned spacecraft system with artificial gravity, featuring a central axial module and four radially arranged habitable modules connected via docking ports. The rotating section, designed to generate centrifugal force, is coupled to the static axial shell through a sealed movable joint. This configuration is expected to enhance crew safety and operational reliability while enabling extended habitation in orbit. (Credit: RSC Energia)

Illustrations included in the patent show a multi‑module structure with dedicated rotation equipment and power systems, suggesting a modular approach rather than a single monolithic station. While the document does not indicate timelines or programmatic commitments, the filing comes as Russia prepares for its post‑ISS strategy and signals continued interest in human‑spaceflight infrastructure that reduces reliance on microgravity environments

MILITARY

CACI Expands Space and Defense Footprint With $2.6 Billion ARKA Group Purchase, Broadens Its Space‑Based Sensing and Intelligence Work

22 December, 2025

U.S. defense contractor and IT solutions provider, CACI International has agreed to acquire space-based tech provider, including laser-guided weapon threat detection systems, ARKA Group, for $2.6 billion in cash, expanding its position in space‑based sensing and intelligence systems. ARKA, owned by Blackstone Tactical Opportunities, develops optical sensors, software processing tools, and other technologies used across U.S. intelligence and defense programs. CACI says the acquisition strengthens its long‑term space strategy by integrating ARKA’s satellite‑focused sensor portfolio with its existing ground‑based data‑processing capabilities, aiming to accelerate delivery of actionable intelligence to national‑security customers.

The deal comes amid rising demand for space, cyber, and surveillance capabilities driven by geopolitical tensions and increased military spending by the United States and its allies. The transaction is expected to close in CACI’s fiscal third quarter of 2026, pending regulatory approval.

Tory Bruno Leaves ULA and Joins Blue Origin to Lead New National Security Group

Tory Bruno, former president and CEO of United Launch Alliance, speaks at a 2024 news conference at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. (Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky)

22 - 26 December, 2025

Tory Bruno, an engineer and longtime aerospace executive, has resigned as CEO of United Launch Alliance after more than a decade leading the Boeing–Lockheed Martin joint venture. ULA announced his departure without offering a detailed explanation, ending a tenure that included the debut of the Vulcan rocket and ongoing competitive pressure from SpaceX. Days later, Blue Origin confirmed Bruno will join the company as president of its newly formed National Security Group, a division focused on defense‑oriented space systems and services. He will report directly to CEO Dave Limp.

The new organization will consolidate Blue Origin’s national‑security launch and in‑space systems work, including programs such as the Blue Ring platform and early deep‑space communications concepts, as the company positions New Glenn for government missions. The move aligns with Blue Origin’s broader push to expand its defense portfolio. ULA has appointed former COO John Elbon as interim CEO while it searches for a permanent successor.

Japan Ministry of Defense Taps Synspective, Axelspace, and iQPS to Join Mitsubishi Electric–Mitsui–JSAT Team to Build Defense Satellite Constellation

25 December, 2025

Japan’s Ministry of Defense has selected Synspective and a consortium of domestic space companies to build and operate a dedicated satellite‑imaging constellation that will give the military priority access to radar and optical data. The program will be executed under a Private Finance Initiative, shifting development and operational responsibility to industry while the government commits to long‑term service purchases.

Under the arrangement, Mitsubishi Electric, Mitsui & Co., and SKY Perfect JSAT will form a joint venture responsible for overall program integration, constellation operations, ground‑segment management, and delivery of imagery services to the defense ministry. Synspective will supply synthetic‑aperture radar data from its growing constellation and contribute SAR‑processing expertise. Axelspace will serve as the project’s sole provider of optical imagery, leveraging its microsatellite platform. iQPS will add additional SAR capacity through its lightweight deployable‑antenna satellites, while Mitsui Bussan Aerospace will support procurement, logistics, and system coordination.

The five‑year contract, expected to run from 2026 to 2031, aims to provide Japan with more timely, weather‑independent imaging for defense and civil‑security applications. The initiative extends Japan’s use of PFI structures into Earth‑observation systems, reflecting a broader global shift toward commercial remote‑sensing capabilities, mirroring global trends accelerated by demand for persistent monitoring and lessons from recent conflicts.

COMMERCIAL

Japan's iQPS Expands Patented Lightweight SAR Fleet as Rocket Lab Completes 2025 With Sukunami‑I Launch

A Rocket Lab Electron rocket launches "The Wisdom God Guides" mission for the Japanese company iQPS from New Zealand on Dec. 21, 2025. (Credit: Rocket Lab)

21 December, 2025

Rocket Lab closed out 2025 with its 21st Electron mission, deploying Japan’s QPS‑SAR‑15 satellite for Earth‑imaging firm Institute for Q-shu Pioneers of Space, Inc. (iQPS). The dedicated launch, named The Wisdom God Guides, lifted off from Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand on December 21 and placed the spacecraft into a 575‑kilometer orbit using Electron’s kick stage. iQPS reported that the satellite made first contact six minutes after deployment, confirming healthy systems and proper orbital insertion.

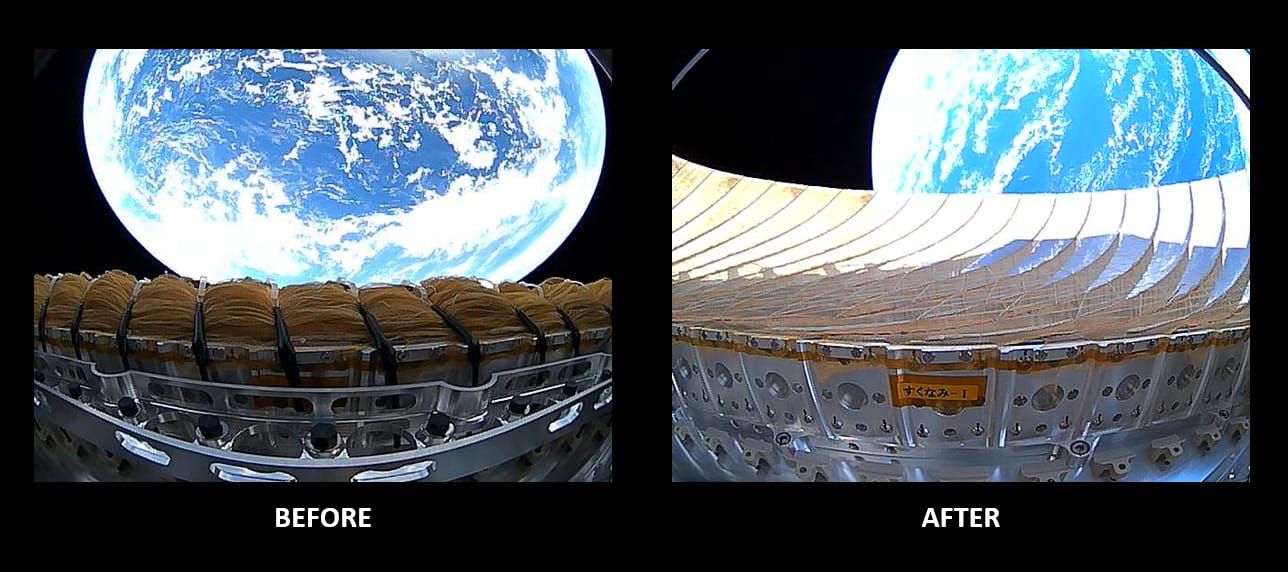

SUKUNAMI‑I deployed its parabolic antenna on Dec. 22 following verification of its healthy status. (Credit: iQPS)

QPS‑SAR‑15, also known as Sukunami‑I, is the latest addition to iQPS’s growing fleet of small, lightweight synthetic‑aperture radar (SAR) satellites. The company’s spacecraft use a proprietary deployable antenna system that folds into a compact form factor for launch and expands in orbit to provide high‑resolution radar imaging. This patented design allows iQPS to field satellites significantly lighter than traditional SAR platforms, enabling more frequent launches and lower deployment costs. iQPS has launched 12 QPS‑SAR satellites to date and plans to expand its constellation to 24 by FY2027 and eventually 36. The full system is designed to provide a “Near-Real-Time Data Provisioning Service,” enabling global observations roughly every 10 minutes and supporting continuous imaging of both stationary features and moving targets such as vehicles, ships, livestock, and human activity.

The mission marked Rocket Lab’s 79th Electron flight and capped a year in which the company achieved a 100% success rate across all launches, reinforcing Electron’s position as a leading small‑lift vehicle. Rocket Lab remains the primary launch provider for iQPS, with additional dedicated missions planned from 2026 onward.

South Korean Innospace’s Hanbit‑Nano Fails on First Orbital Attempt as Company Targets 2026 Relaunch

A view of Innospace's 'Hanbit-Nano' launch vehicle on December 20 at the Alcantara Space Center, in Brazil. (Credit: Innospace)

22 December, 2025

South Korean launch startup Innospace’s first attempt at reaching orbit ended in failure on December 22, when its Hanbit‑Nano rocket suffered an anomaly shortly after liftoff from Brazil’s Alcântara Space Center. The vehicle, carrying eight small satellites and hosted payloads from Brazil, India, and South Korea, appeared to ascend normally before onboard footage showed what looked like an explosion roughly 80 seconds into flight. Innospace later confirmed that the hybrid‑propulsion first stage ignited as expected but experienced an unexplained malfunction about 30 seconds after launch, causing the rocket to fall within a designated safety zone. No injuries or ground damage were reported.

In a letter to shareholders, CEO Soojong Kim said the company is analyzing flight and propulsion data collected during the attempt, emphasizing that real‑world telemetry is essential for maturing its launch system. Innospace plans a second commercial attempt in the first half of 2026 after implementing technical improvements. Hanbit‑Nano is designed to deliver up to 90 kilograms to sun‑synchronous orbit, with larger Hanbit‑Micro and Hanbit‑Mini variants in development. The failure triggered a sharp drop in Innospace’s KOSDAQ‑listed shares.

OPINION

Orbital Data Centers Are Coming and They May Arrive in a Sky Already Too Full

The commercial rush into orbit and the race to build space‑based data centers threaten to eclipse the very sky we study.

By Maharshi Bhattacharya

This animation shows Starcloud’s concept for a 5‑gigawatt space‑based data center powered and cooled by solar and radiator panels measuring roughly 4 km by 4 km. (Credit: Starcloud)

Growing demand for AI and cloud services is putting increasing strain on ground‑based computing infrastructure, where even a mid‑sized data center can consume the electricity load of tens of thousands of households. SatVu’s thermal‑imaging satellites have already shown how concentrated and energy‑hungry these data centers are, mapping their heat signatures across major cities. This demand has pushed technology companies to explore off‑planet alternatives. In November 2025, Google introduced Project Suncatcher, a proposal to deploy an 81‑satellite constellation in low Earth orbit to power space‑based data processing using continuous solar energy. Instead of transmitting power to Earth, the system would beam processed data back down, shifting heat generation into space and reducing reliance on ground‑based facilities. It is here that a question emerges: how much sky are we willing to sacrifice to sustain this escalation.

The satellites in Google’s research effort will carry Google’s TPU (tensor processing units) machine‑learning processors and relay data between one another using laser links. Already running the company’s Gemini 3 model, the chips will be adapted and evaluated for resilience to orbital radiation and thermal extremes. Two prototype spacecraft are planned for launch to low Earth orbit, roughly 400 miles up, in early 2027.

The idea is gaining traction well beyond Google. A recent report from the European Space Policy Institute warns that space‑based data centers are moving from speculation to near‑term industrial planning, with major tech companies already exploring orbital computing as a response to rising energy costs and terrestrial infrastructure limits. The report frames orbital data centers as a potential “backbone” of a second digital era, driven by escalating global data demand and the search for more sustainable compute capacity.

Commercial activity is accelerating as well. U.S.-based, Starcloud, recently launched Starcloud‑1, the first satellite to carry an NVIDIA H100 GPU, a processor roughly 100 times more powerful than any previously flown in orbit. The mission aims to test whether high‑performance AI workloads can run reliably in space and serves as an early step toward the company’s plan for multi‑gigawatt orbital data‑center platforms that would span approximately 4 kilometers/about 2.5 miles in width and length.

Startups such as Lonestar and OrbitsEdge are pursuing early demonstrations, while Axiom Space has discussed hosting data‑processing payloads on future commercial stations. SpaceX and Blue Origin are increasingly positioned to shape the trajectory of orbital data‑center efforts. Emerging reports indicate that a major driver behind the company’s rumored IPO, targeting a $1.5 trillion valuation, is the ambition to finance self‑owned orbital AI infrastructure. This would mark a shift toward operating data‑center platforms in space rather than solely providing connectivity, effectively positioning SpaceX as an “orbital AI company.” SpaceX now says it intends to build space‑based data centers by scaling up its next‑generation Starlink V3 satellites, which feature high‑speed laser links and would rely on Starship for deployment. Blue Origin, while not pursuing data centers directly, is developing large commercial stations and heavy‑lift launch capacity that could support future in‑orbit computing infrastructure. Although most projects remain in early development, 2027 is often cited as a turning point.

Any such systems must contend with an increasingly crowded low Earth orbit. Tens of thousands of trackable objects, and far more too small to monitor, travel at roughly 17,500 miles per hour/28100 kilometers per hour. Operational risks, highlighted by recent debris incidents, including damage to the Shenzhou-20 crew return capsule at China’s Tiangong station, still persist. Google’s preferred sun‑synchronous orbit is among the most congested, raising concerns about collision probability and the potential for cascading debris events described by Kessler syndrome.

Suncatcher’s architecture adds further complexity: its satellites would fly in a tightly packed, one‑kilometer‑wide formation with separations under 200 meters. Large solar arrays increase drag sensitivity (how strongly a satellite’s orbit is affected by the tiny but persistent “air resistance” that still exists in low Earth orbit), while fluctuating space‑weather conditions complicate station‑keeping, that is keeping the satellite in its intended orbit or formation. A single impact could disrupt the entire cluster and generate extensive new debris. Meeting this risk profile may require autonomous, real‑time avoidance capabilities far beyond what most constellations currently employ.

However, regulators are beginning to respond. The FCC now requires post‑mission disposal within five years, and policymakers are considering orbital‑use fees to fund debris‑removal missions. As commercial constellations expand and new sectors, such as orbital data centers, seek access to already crowded orbital shells, long‑term viability may depend as much on governance and debris‑removal infrastructure as on engineering breakthroughs. This raises a second question with increasing urgency: who decides what orbit is for when commercial expansion outpaces public oversight.

Yet this push toward orbital infrastructure is unfolding alongside a quieter crisis: the night sky itself is disappearing. Astronomers are already warning that the rapid growth of commercial constellations is eroding the night sky as a scientific resource. Observatories from the Atacama to Hawaii report rising interference from satellite streaks, and new modeling shows that by the 2030s, most deep‑space exposures could be partially unusable.

Orbital data centers may be a “momentary silver bullet” for the problems associated with terrestrial facilities, but more nuanced questions emerge as well. Large orbital compute platforms could alter local thermal environments or contribute to sky brightness, raising concerns about cumulative environmental effects. They would require high‑bandwidth laser or RF links, adding pressure to already contested spectrum allocations overseen by the ITU. On the compliance front, current liability conventions were not designed for dense compute constellations, leaving it unclear who pays when a high‑value platform is struck by debris. As more commercial infrastructure moves into orbit, public trust and transparency may become as important as technical readiness.

The next phase of orbital expansion may require not just technical innovation, but a more visible intergovernmental effort to manage space as a shared and increasingly fragile domain. As commercial ambitions accelerate, the question is whether public institutions can build the cooperative frameworks needed to keep Earth’s orbit usable for generations.

Despatch Out. 👽🛸