Hello there, {{First_Name|Explorer}}.🚀

Happy orbital reset! New developments this week in science, governance and commerce; some exciting, others, questionable.

Click here for the full newsletter experience. ⬇️⬇️

IMAGES

Solid-State Long-Range Radar System LRDR : US Space Force

The U.S. Space Force, on December 4 formally took operational control of the Long Range Discrimination Radar (LRDR) at Clear Space Force Station in Alaska, marking a major step in expanding the service’s missile‑warning, tracking and targeting (MWT&T) as well as Space Domain Awareness (SDA) capabilities. The solid‑state system, accepted by the Combat Forces Command after the Missile Defense Agency completed LRDR's operational trial period, is designed to improve interceptor precision, shorten response times, and strengthen U.S. homeland defense against long‑range ballistic missile threats. The SDA functionality is slated for operational acceptance following a trial period with Command and Control, Battle and Management Communications and the National Space Defense Center.

The newly released image shows the radar complex under heavy winter snow, highlighting the remote conditions in which the system will operate. The radar is built for precision discrimination, enabling it to distinguish lethal from non‑lethal ballistic‑missile objects in a crowded operating environment. It increases mission effectiveness by simultaneously searching, tracking, and discriminating multiple long‑range threats, supplying precise tracking and hit‑assessment data to the Ground‑Based Midcourse Defense Fire Control System. Its modular architecture allows future upgrades without major redesigns, and continuous threat monitoring maintains operational readiness even during maintenance, reducing system downtime. (Credit: US Space Force)

Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre, South Australia : Landsat 8

Heavy rains across Queensland in early 2025 sent rare floodwaters coursing through Australia’s Channel Country, eventually reaching Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre, the continent’s lowest and typically dry salt basin. These northern river systems are the primary pathways that feed Lake Eyre during major flood years, carrying water south across the Channel Country before it spreads into the basin. By May, satellite sensors detected water flowing in from northern tributaries, filling the lake to levels seldom seen in recent decades. The system continued to expand through winter before inflow slowed in October as temperatures rose and evaporation began to dominate. By December, local observers reported that feeder rivers had dried and lake levels were rapidly receding. (Credit: Landsat 8)

As the water retreated, Landsat 8 imagery captured striking color changes across the basin, produced by shifting sediments, salinity, and microbial activity exposed during the drying phase. The episode highlights the sensitivity of Lake Eyre’s hydrology to extreme rainfall events and the speed with which the landscape transitions between inundation and desiccation in one of Australia’s most arid regions. The two deepest parts of the lake, Belt Bay and Madigan Gulf, still contained some water, which took on greenish and reddish hues, respectively. (Credit: Landsat 8)

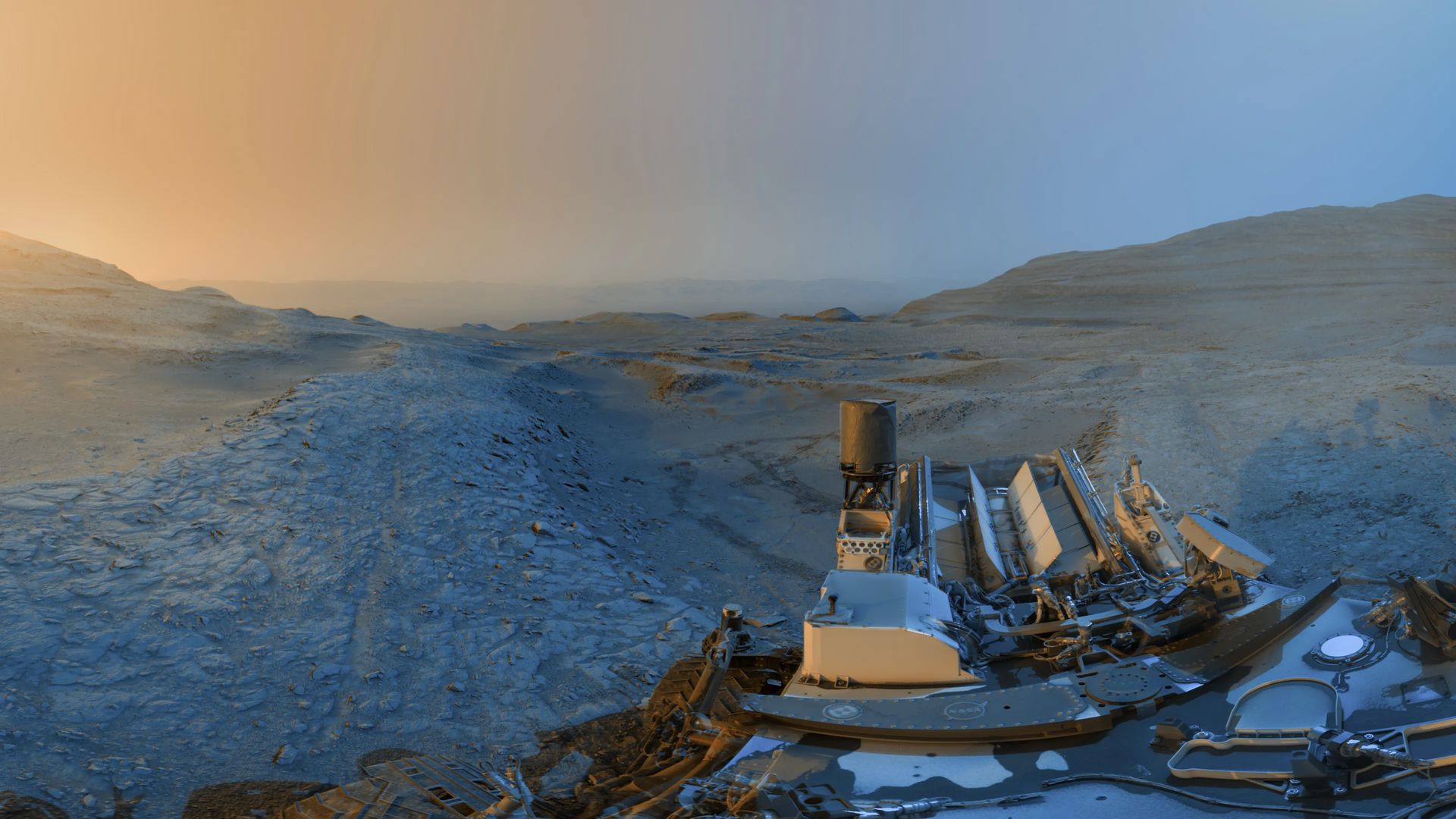

Postcard from Mars : Curiosity Rover

NASA’s Curiosity rover has released a new composite “holiday postcard” from its position on the slopes of Gale Crater, created by stitching together two panoramas taken on Nov. 18, 2025, during the rover’s 4,722nd and 4,723rd Martian days. The images were captured at 4:15 p.m. and 8:20 a.m. local Mars time, then merged to show the contrasting hues of a Martian afternoon and morning, blue tones from the early panorama and yellow from the later one, added as an artistic interpretation to highlight landscape details. (Credit: NASA)

N159 Star-Forming Region in the Large Magellanic Cloud : Hubble Space Telescope

Hubble’s image shows a section of N159, one of the most massive star‑forming clouds in the Large Magellanic Cloud, located about 160,000 light‑years away in the constellation Dorado. The region is dominated by cold hydrogen gas shaped into ridges and filaments, where gravity compresses material into new stars. Hot, high‑mass young stars embedded within the cloud illuminate their surroundings with red light, while their radiation and stellar winds carve out bubble‑like cavities, clear signatures of active stellar feedback. This view captures only a portion of the larger N159 complex, which spans roughly 150 light‑years across. (Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Indebetouw)

Another image captured by Hubble, is a neighboring region of the N159 star‑forming complex. The scene is dominated by thick clouds of cold hydrogen gas arranged in ridges, cavities, and filaments, revealing the structure of one of the dwarf galaxy that is the largest of the small galaxies that orbit the Milky Way – Large Magellanic Cloud’s most active stellar nurseries. Embedded within these dense pockets, newly formed stars illuminate their surroundings, with intense radiation causing the hydrogen to glow in deep red tones.

The brightest areas mark clusters of hot, massive young stars whose ultraviolet light and powerful stellar winds are reshaping the cloud, carving out bubble‑like voids and hollowed cavities, clear signatures of stellar feedback at work. Captured in a parallel field to the previous image, the view adds context to the broader N159 complex, illustrating how star formation and feedback interact across neighboring regions of the same molecular cloud system. (Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Indebetouw)

Colliding Spiral Galaxies : James Webb Telescope & Chandra X-Ray Observatory

Mid‑infrared data from the James Webb Space Telescope (in white, gray, and red) and X‑ray observations from NASA’s Chandra X‑ray Observatory (in blue) reveal two interacting spiral galaxies, IC 2163 and NGC 2207, captured in a new composite released on Dec. 1, 2025. The pair grazed past one another millions of years ago, triggering tidal distortions, shock‑heated gas, and regions of intensified star formation visible across the system. Webb’s infrared imaging highlights dust‑rich structures and warm interstellar material, while Chandra’s X‑ray data traces high‑energy processes associated with stellar remnants and compact objects embedded in the collision zone.

Although the galaxies appear frozen in a moment of contact, their interaction is ongoing; gravitational forces will eventually draw them together, leading to a full merger billions of years from now. The composite offers a multi‑wavelength view of how large‑scale galactic encounters redistribute gas, reshape spiral structure, and drive long‑term evolutionary change. (Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Infrared: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI/Webb; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/L. Frattare)

NGC 4388 Galaxy : Hubble Space Telescope

This Hubble image captures NGC 4388, a spiral galaxy about 60 million light‑years away in Virgo constellation. Seen nearly edge‑on, the galaxy reveals a plume of gas extending from its nucleus, an outflow not visible earlier in Hubble’s 2016 observations. The feature likely formed as the galaxy moves through the Virgo Cluster’s hot intracluster medium, which strips gas from its disk and leaves it trailing behind.

What makes the plume glow is less certain. Some of the ionization may come from the galaxy’s central supermassive black hole, whose accretion disk emits intense radiation, while shock waves farther out may energize more distant filaments. New multi‑wavelength data highlight this ionized gas, drawn from observing programs focused on galaxies with active black holes. (Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, S. Veilleux, J. Wang, J. Greene)

SCIENCE

Three Iranian Satellites Launched on Russian Soyuz Rideshare from Vostochny alongside UAE and International Payloads

29 December, 2025

Iran has reported that three domestically built satellites, Paya, Kowsar and Zafar‑2, were launched into orbit aboard a Russian Soyuz -2.1b rocket from the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Siberia on December 28. According to Iranian state media, the spacecraft, placed in roughly 500‑kilometer orbits, are designed for Earth‑observation tasks including monitoring natural resources, agriculture and environmental conditions. Paya, at 150 kilograms, is described as Iran’s heaviest imaging satellite to date.

The launch was part of a larger rideshare mission that deployed 52 satellites in total, including two Russian Aist‑2T Earth‑observation spacecraft, as well as a small satellite built for the UAE‑based Sputnix Group, multiple cubesats from Russian universities, and a climate‑ and space‑weather‑monitoring satellite for the Russian Hydrometeorological Service. Roscosmos described the manifest as a mix of domestic and foreign payloads, continuing Moscow’s reliance on commercialized multi‑manifest Soyuz missions despite geopolitical isolation. Iranian officials framed their participation as evidence of domestic technological progress achieved under Western sanctions, stressing that Paya, Kowsar, and Zafar‑2 were designed and built by Iranian engineers.

Russia’s state media highlighted the mission as another example of expanding Moscow–Tehran cooperation in space, following multiple Iranian launches on Russian rockets earlier in 2025. The partnership continues to draw scrutiny given dual‑use concerns surrounding Iran’s aerospace program.

IMAP, Carruthers Observatory and TRACERS Progress Through Early Operations in NASA’s Heliophysics Program

Animated visualization showing energetic particles and cosmic rays interacting with the heliosphere — the vast bubble carved out by the solar wind — and tracing back toward the heliopause, the boundary where the Sun’s influence gives way to interstellar space. The GIF illustrates how NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) will detect energetic neutral atoms and map the structure of this boundary region from its orbit around the Earth–Sun L1 point, revealing how particles are accelerated and how the heliosphere shields the solar system. The animation depicts the heliosphere as a vast, dynamic structure shaped by solar wind and interstellar material. (Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Conceptual Image Lab/Walt Feimer)

31 December, 2025

Two NASA heliophysics missions launched together in September, the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) and the Carruthers Geocorona Observatory, are progressing toward routine operations, according to updates shared at the American Geophysical Union meeting. Both spacecraft, launched on a Falcon 9 alongside NOAA’s Space Weather Follow‑On L1 satellite, are still en route to their planned halo orbits around the Earth–Sun Lagrange L1 point, about 1.5 million kilometers away. Early data returns indicate that instruments are performing as expected.

A third mission, the Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites (TRACERS), launched separately earlier in the year, has started limited science operations focused on magnetic reconnection in Earth’s polar cusp, though one of its two spacecraft remains partially impaired, reducing the mission’s ability to perform coordinated measurements.

IMAP is beginning instrument checkouts as it travels toward its halo orbit around the Earth–Sun L1 point, where it will map the boundary of the heliosphere and study how particles are accelerated at its edge. The heliosphere is the vast bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields created by the Sun that surrounds and protects the solar system from much of the incoming interstellar radiation. The Carruthers Geocorona Observatory is calibrating its ultraviolet imager to measure Earth’s extended hydrogen atmosphere, or geocorona, and its variability. NOAA’s Space Weather Follow‑On L1 mission is conducting early tests of its solar wind and coronagraph instruments ahead of operational space‑weather forecasting duties.

The mixed status of the fleet comes amid broader concerns about funding stability and workforce continuity in NASA’s heliophysics division, which has faced delays and budget pressures affecting mission development pipelines.

China’s End‑of‑Year Activity Highlights Guowang, Fengyun‑4C, Shijian and Tianhui Launches and Long March 10B Reusable Rocket Development

29 December, 2025

China closed 2025 with a record 92 orbital launches, that advanced both its operational satellite programs and its long‑term infrastructure plans. The year’s final missions included deployments for the Guowang broadband megaconstellation, which continued to receive batches of satellites on consecutive Long March flights as China works to meet International Telecommunication Union filing deadlines and internal deployment targets. U.S. tracking identified nine additional satellites inserted into roughly 910‑kilometer, 50‑degree orbits. The cadence also supported a range of national priorities, from Earth‑observation to deep‑space science, including the launch of the Fengyun‑4C geostationary meteorological satellite from Xichang, intended to replace the aging FY‑4A and operate jointly with FY‑4B to strengthen severe‑weather and space‑weather monitoring. The China Meteorological Administration highlighted improved imaging and atmospheric‑sounding capabilities designed to enhance early‑warning systems for extreme weather events.

The Long March 7A Y7 rocket lifted off from Launch Complex 201 at the Wenchang Space Launch Site on December 29, 30, 2025. (Credit: via China-in-Space)

29 December, 2025

Additional end‑of‑year missions included the Tianhui‑7 land‑survey satellite and the Shijian‑29A/B technology‑demonstration pair, which Chinese authorities described as supporting new space‑target detection experiments. These flights rounded out a launch cadence that also featured an emergency Shenzhou mission to Tiangong and the Tianwen‑2 near‑Earth asteroid sample‑return launch, according to domestic reporting.

31 December, 2025

Alongside operational missions, China is preparing a new generation of reusable launch vehicles intended to increase throughput for megaconstellation deployment and support future crewed lunar infrastructure. Official statements indicate a planned first flight of a cargo‑optimized variant of the new crew launch vehicle in the first half of the year. China Rocket, a commercial spinoff of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), stated in December that it aims to conduct the first flight of a 5‑meter‑diameter reusable liquid‑propellant launcher in early 2026. The vehicle appears to draw heavily on technologies from the Long March 10A, the crew‑rated launcher under development for the Mengzhou spacecraft and China’s broader lunar program. A variant shared at the Wenchang International Aviation and Aerospace Forum as Long March 10B is expected to deliver roughly 11,000 kilograms to a 900‑kilometer, 50‑degree orbit, a performance class aligned with Guowang deployment needs. The rocket may incorporate a methane–liquid oxygen upper stage, and CALT has unveiled a maritime recovery vessel equipped with a net‑capture system for retrieving returning boosters.

Achieving reliable reusability is viewed as essential for sustaining the launch rates required for Guowang and for supporting China’s goal of landing astronauts on the Moon before 2030.

Reusable‑launcher development is now distributed across multiple Chinese institutions. The Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) debuted the reusable Long March 12A earlier in the year, though its propulsive landing attempt was unsuccessful. Commercial firms, including Landspace, which completed China’s first orbital‑class recovery attempt in December, are advancing their own methane‑fueled systems, with vehicles such as Pallas‑1, Kinetica‑2, Tianlong‑3, and Nebula‑1 targeting inaugural flights in 2026.

Space Debris Risks Keep Emerging as Starlink Lowers Orbits and SpainSat NG II Suffers Particle Impact During Transfer

Space operators entered 2026 facing a widening set of debris‑related risks across low Earth orbit, geostationary transfer corridors, and even commercial airspace.

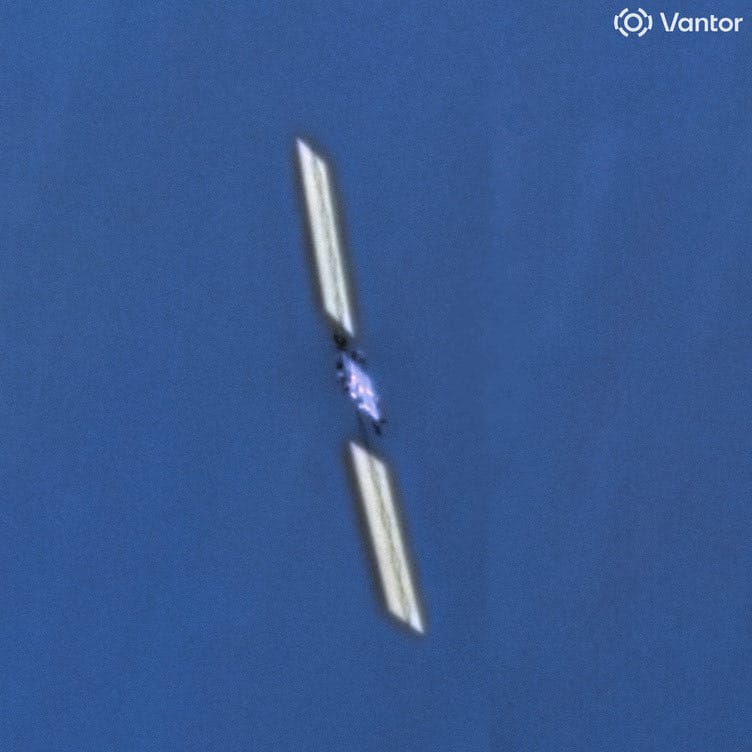

A high‑resolution image from Vantor’s WorldView‑3 satellite shows a malfunctioning SpaceX Starlink spacecraft after an in‑orbit anomaly on December 17 caused it to lose contact and vent its propulsion tank.

The failure left the satellite tumbling and descending toward Earth, where it is expected to burn up in the atmosphere within weeks, according to SpaceX. Vantor captured the photo from about 150 miles away to help assess the satellite’s condition, offering a rare close‑up look at a damaged spacecraft in low Earth orbit. (Credit: Vantor)

1 January, 2026

SpaceX announced it will lower the orbits of roughly 4,400 Starlink satellites from about 550 kilometers to 480 kilometers throughout 2026, a move the company frames as a safety measure intended to reduce long‑term debris persistence and collision probability in a thinning atmosphere during solar minimum, which is the period in the Sun’s 11‑year cycle when solar activity drops and the upper atmosphere cools and contracts, reducing natural drag on satellites and debris. Starlink engineering vice president Michael Nicolls said the shift will shorten ballistic decay times, i.e., speed up how quickly satellites naturally deorbit by more than 80 percent and concentrate operations in a region with fewer planned constellations and debris objects. The decision follows a December anomaly in which a Starlink satellite malfunctioned and shed debris at 418 kilometers before rapidly descending.

1 January, 2026

The broader debris environment remains strained. Over 140 million fragments are estimated to orbit Earth, and 2025 saw a high‑profile emergency when China’s Shenzhou‑20 spacecraft discovered a cracked window attributed to a sub‑millimeter debris strike during pre‑return checks. The incident forced China to delay the crew’s return and launch an uncrewed Shenzhou‑22 as a replacement vehicle, underscoring the limits of global tracking systems and the vulnerability of human spaceflight to untrackable particles.

Debris risks are not confined to orbit. Experts warn that falling space junk, primarily rocket bodies and decaying satellites, now reenters the atmosphere roughly once per week, with a small but rising probability of intersecting commercial flight paths. While most objects burn up, surviving fragments ranging from dust‑sized particles to intact propellant tanks can pass through airspace used by aircraft, prompting renewed calls for improved forecasting and international coordination.

SpainSat NG II undergoing pre‑launch preparations ahead of its October 2025 liftoff. (Credit: Airbus Defence and Space)

3 January, 2026

Even high‑value geostationary missions are not insulated. Spain’s new SpainSat NG II military communications satellite—built by Airbus Defence and Space and Thales Alenia Space as part of the SpainSat NG program, suffered an external impact from an untrackable “space particle” at roughly 50,000 kilometers while raising its orbit following its late‑October 2025 launch. Operator Hisdesat and majority partner Indra Group activated contingency plans after disclosing the anomaly in early January 2026, while engineers assess potential damage and mission implications. European reporting similarly notes that the strike occurred during transfer operations and may affect long‑term service availability.

The frequency of occurrence of these incidents is a worrying sign of a debris environment that is expanding in scale and consequence, pressuring operators to adopt mitigation strategies while exposing persistent gaps in global governance and tracking infrastructure.

GOVERNANCE

NSF‑Funded National Center for Atmospheric Research at Risk as Trump Administration Weighs Lab Breakup, Citing “Climate Alarmism”

The National Center for Atmospheric Research is facing pressure from the White House. (Credit: Tim Farley/Wikimedia Commons)

The Trump administration has signaled plans to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), a major U.S. hub for climate, weather, and atmospheric modeling.

Climate scientists attending the American Geophysical Union meeting learned that the Trump administration is considering dismantling the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), a leading U.S. hub for climate and weather research. The news came through a post on X on December 16, from Russell Vought, director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, and arrived without prior notice to NCAR, the National Science Foundation, or UCAR, which manages the center, according to UCAR president Antonio Busalacchi. Vought’s post described NCAR as a major source of “climate alarmism” and suggested that core functions, including weather research, could be transferred to another organization or location.

The administration has not detailed the legal or operational path for doing so. NCAR, funded by the National Science Foundation and managed by the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), supports global climate modeling, severe‑weather forecasting, and research that underpins both civilian and national‑security applications.

UCAR said it has received no formal guidance and emphasized NCAR’s role in protecting lives, property, and economic activity. Scientific organizations, including the American Astronomical Society, warned that dismantling NCAR would disrupt research infrastructure relied upon across Earth and space sciences, from atmospheric modeling to heliophysics. Protests are underway in Colorado, joined by elected officials supporting NCAR, with many warning that the proposal could weaken U.S. scientific capacity.

European Space Agency Hit by Cyberattack on External Servers as Hackers Claim 200GB Data Breach

Hacker 888’s post on DarkForums. (Credit: Hackread.com)

30 December, 2025

The European Space Agency (ESA) has confirmed and is now investigating a cybersecurity breach after a threat actor known as “888” claimed to have stolen roughly 200 gigabytes of internal data from external collaboration servers. ESA confirmed that a “very small number” of servers located outside its corporate network were compromised, describing them as systems used for unclassified collaborative engineering activities. The agency said no classified environments were affected and that the compromised infrastructure was isolated from core networks.

The attacker alleges they maintained access for about a week in mid‑December and has attempted to sell the data on cybercrime forums, posting screenshots as proof. The claimed material includes source code, access tokens, configuration files, and confidential documents. ESA has launched a forensic analysis and implemented mitigation measures while notifying relevant partners.

The incident is not unprecedented for ESA and has faced prior incidents, including a holiday‑season compromise of its online store last year and a 2015 breach of several agency domains that exposed subscriber and staff data.

MILITARY

Space Force Issues RFI for Heavy‑Lift Launch Infrastructure at Vandenberg’s SLC‑14 Amid $212M Base Network Upgrade to CACI

29 December, 2025

The U.S. Space Force is advancing parallel efforts to expand its launch infrastructure and modernize the digital networks that support its operations. At Vandenberg Space Force Base, the service issued a request for information for potential development of Space Launch Complex‑14 (SLC-14), an undeveloped site identified as the base’s most viable location for heavy and super‑heavy launch vehicles. The former have payload capacities of 20,000 to 50,000 kilograms while the latter are those with capacities greater than 50,000 kilograms to low Earth orbit. The RFI seeks proposals from companies capable of financing, constructing, and operating a new launch facility near the southern tip of Vandenberg, with requirements for “sufficient financial maturity” and vehicles able to begin operations within five years. The Space Force also signals a preference for systems not already flying from Vandenberg, aiming to diversify launch providers and add capabilities such as point‑to‑point transport or payload return.

The criteria appear to align most closely with SpaceX’s Starship, which meets the super‑heavy classification and has potential national‑security applications in high‑inclination orbits. Other heavy‑lift developers, including ULA and Blue Origin, already have access to or have studied alternative Vandenberg sites, though no lease has been issued for Blue Origin’s previously reviewed SLC‑9 concept. Any SLC‑14 lease would require a full environmental impact statement and launch‑safety analysis before approval.

In parallel, the Space Force is pursuing a broad overhaul of its base‑level digital infrastructure. Under the Air Force‑led Base Infrastructure Modernization (BIM) program, U.S. defense contractor and IT solutions provider, CACI International, received a five‑year task order worth up to $212 million to upgrade network systems across all 14 Space Force installations. The work includes modernizing classified and unclassified networks, implementing zero‑trust security architectures, and supporting cloud‑based operations. BIM is structured as a 10‑year, $12.5 billion IDIQ contract vehicle intended to replace aging systems that were not designed for current cybersecurity demands or data volumes.

COMMERCIAL

Planet Partners with Google on Project Suncatcher to Demonstrate Early TPU‑Powered Orbital Data Center Technologies

Credit: Planet Labs

Planet is positioning itself for the emerging market of orbital data centers, partnering with Google on Project Suncatcher to test whether AI compute infrastructure can operate effectively in space. A two‑satellite demonstration is slated for 2027 that will test whether Google’s tensor processing units (TPU) chips can operate reliably in space. The mission builds on Planet’s new Owl satellite bus and focuses on core technical hurdles, thermal management, radiation tolerance, and high‑bandwidth intersatellite links, that must be solved before large‑scale in‑orbit compute becomes viable. Planet argues its experience deploying hundreds of small satellites gives it an operational edge, though the company acknowledges Suncatcher remains early‑stage R&D.

Google’s long‑term concept envisions clusters of dozens, eventually thousands, of satellites in sun‑synchronous orbits to supply continuous solar power for AI workloads. The idea reflects a broader industry shift: SpaceX, Blue Origin, and several startups are pursuing similar experiments as terrestrial data centers face energy and scaling constraints. Significant challenges remain, but companies increasingly frame orbital compute as a plausible medium‑term infrastructure path rather than a speculative concept. Both companies frame it as groundwork for a potentially large future market.

Celestis Partners with Stoke Space for Second Deep‑Space Memorial Flight

Celestis has booked Stoke Space’s fully reusable Nova rocket for the mission, called Infinite Flight, scheduled for late 2026 from Cape Canaveral. (Credit: Stoke Space)

29 December, 2025

Celestis, a U.S.-based memorial spaceflight provider that sends cremated remains or DNA into space as a unique form of burial or tribute, has booked 100% rapid reusability startup, Stoke Space’s Nova rocket to fly its second deep‑space memorial mission, further expanding a niche launch market built around sending symbolic human remains beyond Earth. The mission, called Infinite Flight, is scheduled for late 2026 from Cape Canaveral and will place the payload into a permanent heliocentric orbit, potentially reaching distances of up to 185 million miles / 297.7 kilometers from Earth. For reference, the Sun is 93 million miles / 150 million kilometers from Earth. It follows the company’s 2024 Enterprise Flight, which carried remains of public figures and private customers on a similar one‑way trajectory.

For Stoke Space, the contract offers an early commercial use case for Nova, a fully reusable medium‑lift rocket, meaning both stages return, refuel, and fly again within 24 hours, expected to attempt its first orbital test in 2026.

LandSpace Moves Toward US$1 Billion Shanghai IPO to Fund Reusable Methane Rocket Development

A recovered component from a modified ZQ‑2 rocket, launched in 2023, is displayed for visitors at LandSpace’s Beijing facility on February 24, 2025

31 December, 2025

China-based private launch firm LandSpace is moving toward a US$1 billion initial public offering (IPO) on Shanghai Stock Exchange’s Nasdaq-style STAR Market, becoming the first pre‑revenue rocket company accepted under newly eased listing rules that support firms developing reusable launch vehicles. The company aims to raise 7.5 billion yuan to scale production of its methane‑fueled Zhuque‑3 rocket and advance reusability efforts, despite its early booster‑landing tests ending without recovery. Regulatory changes allow commercial rocket companies to bypass traditional profitability requirements if they demonstrate progress on medium‑ or large‑class reusable systems.

LandSpace reported modest revenue but significant losses in 2025, hinting at the capital‑intensive nature of China’s emerging commercial launch sector. The IPO push comes as Beijing encourages private aerospace investment to compete with global players and reduce reliance on state‑owned incumbents. LandSpace positions itself as a domestic challenger to SpaceX, though its technology remains unproven at scale and the company faces execution, regulatory, and market‑demand risks as China’s commercial launch landscape rapidly expands.

Space Forge Generates World‑First 1,000°C Plasma in Orbit on Free‑Flying ForgeStar‑1 Commercial Manufacturing Platform

Space Forge deployed its ForgeStar-1 in-space manufacturing satellite in June 2025, along with other payload, on SpaceX's Transporter-14 mission. (Credit: Space Forge)

31 December, 2025

UK-based startup, Space Forge has achieved a key milestone in its effort to commercialize in‑space manufacturing, confirming it generated plasma aboard its ForgeStar‑1 satellite at an altitude of over 515 km / 300 miles, described as a world‑first for a free‑flying commercial platform. The orbital furnace reached roughly 1,000°C / 1832°F , demonstrating that the extreme thermal conditions required for gas‑phase crystal growth can be created and controlled autonomously in low Earth orbit. The company aims to use microgravity and vacuum conditions to produce wide‑ and ultra‑wide‑bandgap semiconductor materials with far higher purity than Earth‑grown equivalents, potentially improving performance in power electronics and communications systems.

Image showing the first plasma produced on Space Forge’s ForgeStar‑1, demonstrating the satellite’s high‑temperature furnace capability. (Credit: Space Forge)

“Wide‑ and ultra‑wide‑bandgap semiconductor materials” are advanced semiconductors that can handle far higher voltages, temperatures, and power than normal silicon. They do this because they have a larger bandgap, meaning electrons need more energy to move, making the material tougher, more efficient, and better for high‑power electronics.

Wide‑bandgap examples: silicon carbide, gallium nitride

Ultra‑wide‑bandgap examples: gallium oxide, diamond‑based semiconductors

Space Forge is interested in them because microgravity can help grow these crystals with fewer defects, which is hard to achieve on Earth.

The test was operated remotely from Space Forge’s center in Cardiff and confirms that the satellite’s heating and thermal‑control systems work as intended. Even with this milestone, the broader idea of industrial manufacturing in orbit still faces major questions: cost, scalability, and how to reliably return finished materials to Earth. Space Forge sees ForgeStar‑1 as a first step toward proving that space‑based production can eventually become commercially viable.

Eartheye Space Lands Asia‑Pacific Earth‑Observation Contract for High‑Resolution, Multi‑Sensor Satellite Data

Credit: Eartheye Space

2 January, 2026

Eartheye Space has secured a new contract in the Asia‑Pacific region to supply imagery and data drawn from a network of hundreds of Earth‑observation satellites. The agreement, whose customer and value remain undisclosed, includes access to both imaging and non‑imaging sensors and supports multi‑sensor tasking with resolutions reportedly reaching 15 centimeters per pixel. The Singapore and Australia‑based startup, founded in 2022, positions the deal as a milestone for its platform, which aggregates tasking across more than 500 commercial and government satellites.

The company has been expanding beyond traditional Earth‑observation services. At the International Astronautical Congress in September, Eartheye announced plans to offer self‑service tasking for sensors pointed into space, broadening its data‑collection model. Government and defense users currently account for roughly three‑quarters of its revenue, with commercial customers making up the remainder and the deal likely carries dual‑use applications with strategic or security‑focused components. Eartheye emphasizes rapid delivery as a differentiator, claiming it can process and return requested information within minutes.

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

Rare Free‑Floating Exoplanet Detected 10,000 Light‑Years Away as Astronomers Achieve First-Ever Mass Measurement

An illustration showing a planet bending the light of a background star through gravitational lensing. (Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk/OGLE)

An international team of astronomers led by Subo Dong of Peking University in China have identified a rare free‑floating exoplanet roughly the size of Saturn and, for the first time, measured both its mass and distance from Earth. The object, located nearly 10,000 light‑years away toward the Milky Way’s bulge, was detected through gravitational microlensing using a combination of ground‑based observatories and the Gaia space telescope. This dual‑perspective alignment allowed researchers to overcome the long‑standing “mass‑distance degeneracy” that typically limits microlensing studies, enabling a direct mass estimate of about 70 Earth masses, or roughly 22% of Jupiter’s mass.

An illustration of the microlensing event KMT‑2024‑BLG‑0792/OGLE‑2024‑BLG‑0516, captured simultaneously by ground‑based telescopes and the Gaia spacecraft. (Credit: J. Skowron / OGLE)

The planet appears to occupy the so‑called “Einstein desert,” a size range where few rogue planets have been confirmed. Researchers suggest it was likely formed in a planetary system before being ejected through gravitational interactions. The discovery adds evidence that the galaxy may host large numbers of such unbound worlds and demonstrates the growing capability of combined Earth‑ and space‑based microlensing campaigns. The findings were published in the journal Science.

Microlensing occurs when a massive object—such as a star, brown dwarf, or planet—passes in front of a more distant star and briefly magnifies its light. The foreground object’s gravity acts like a lens, bending and focusing the background starlight.

Because the lensing effect depends on the mass of the foreground object rather than its brightness, microlensing can reveal faint or invisible bodies, including free‑floating planets that emit no light of their own. Microlensing is gravitational lensing, but on a small scale and detected through brightness changes rather than visible distortions.

Despatch Out. 👽🛸